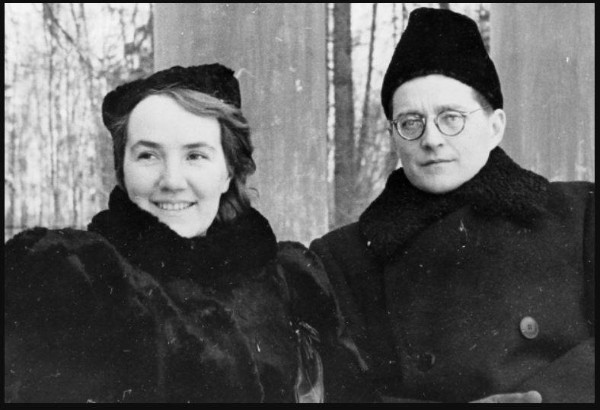

Credit: http://sacramentovocalmusic.com/

In the early 1950’s during the days when my father was a hopeful candidate for the Toronto Symphony, there was no formal audition and no committee. Musicians showed up at the Maestro’s hotel room to play whatever was thrown at them. My father, a recent refugee from war torn Europe, had two strikes against him. He had been waiting two years to join the musician’s union, required for any gigs. My Dad knew too that the orchestra was reluctant to hire a “foreigner.” Meanwhile he washed cars and cleaned office buildings. One day he received a clandestine call. “George,” the caller whispered, “The audition is tomorrow. Show up and don’t tell anyone I was the one who called you about it.” The next day Dad took the bus to the unfamiliar downtown area, nervous about finding the hotel let alone playing his best with so little notice and soggy fingers from his part-time work. He was the last candidate to arrive at the hotel. Dad played the Haydn D major concerto for Sir Ernest MacMillan, a piece that is technically and musically demanding. Then he was asked to sight-read several orchestral works. My father got the job. At the time, the entire symphony season was 24 weeks. He earned $125. a week. (He had to continue to wash cars.)

Today the process is much different. Committees are elected to listen to candidates. The preliminary round is usually behind a screen so the gender, age or race of the musicians is unknown and identities are anonymous— a colleague might otherwise be recognized. Musicians come from far and wide for one opening and rarely play more than a few moments initially. There is immense pressure not miss one note, not to start shakily, not to lose concentration for an instant.

My audition for associate principal cello of the Indianapolis Symphony was a true test of grit and determination. I had prepared the required list for weeks. After I had performed my concerto—the Variations on a Rococo Theme of Tchaikovsky, and all of the excerpts including the famous recitative from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Ein Heldenleben by Strauss, and several solos from the repertory— the principal cello of the orchestra came onstage with her part of Shostakovich Symphony No. 1 which was not on the list. She asked me to sight-read the exposed cello solo from her music, using her bowings and fingerings! I had never heard of being asked to play someone else’s fingerings before but I was ready to play it upside down and backwards if need be. It was a good thing that I had prepared the way I did. I was ready to be flexible: to play the excerpts in any tempo, with a variety of bowing styles and differing dynamics. I got the job.

My audition for associate principal cello of the Indianapolis Symphony was a true test of grit and determination. I had prepared the required list for weeks. After I had performed my concerto—the Variations on a Rococo Theme of Tchaikovsky, and all of the excerpts including the famous recitative from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Ein Heldenleben by Strauss, and several solos from the repertory— the principal cello of the orchestra came onstage with her part of Shostakovich Symphony No. 1 which was not on the list. She asked me to sight-read the exposed cello solo from her music, using her bowings and fingerings! I had never heard of being asked to play someone else’s fingerings before but I was ready to play it upside down and backwards if need be. It was a good thing that I had prepared the way I did. I was ready to be flexible: to play the excerpts in any tempo, with a variety of bowing styles and differing dynamics. I got the job.Having been on both sides of the process, I think it’s very important to share some tried and tested tips. Here are ten:

1 – Always be prepared. Make certain you haven’t inadvertently learned a wrong rhythm or note.

2 – Know the score, the style and what else is going on in the piece. It is quite obvious to the committee when you interpret your part with an awareness of where your line fits in the whole. Show the differences between the styles of Mozart, Debussy, Brahms or Stravinsky.

3 – Mentally prepare with positive thoughts. Imagine the scene. Visualize playing well, feeling confident and being relaxed.

4 – Be ready to play your excerpts at different tempos and in different styles, off the string or on the string, in one breath or phrased differently.

5 – Practice with a metronome so you can play strictly in rhythm counting the rests too.

6 – Concentrate on playing with a gorgeous sound and being musical not on what the committee may think or who else might be auditioning.

7 – Exaggerate the dynamics. Do exactly what the sheet music indicates— as far as dynamics, style indications, and length of notes. Do not play freely or with rubato if it is not indicated in the music.

8 – The Maestro may want to conduct you in the audition. Maintain keen eye contact, respond to their guidance and do exactly as they indicate. If there is a chamber music component to your audition, the committee is looking for your responsiveness and interaction with the other players.

9 – Don’t forget to breathe. Take a moment before each excerpt to focus on the work you must play next. If you do flub it, know you are not alone. Stop and ask if you might try it again.

10 – Stage “mock auditions” with scary colleagues and friends. The constructive criticism will be invaluable. Have them ask randomly for the orchestral excerpts so you can practice switching gears quickly.

Despite all the preparation, on a given day they may be looking for green and you are purple. Sometimes our playing just doesn’t fit into the style of that orchestra. The standards today are very high but you are an individual with special qualities to add. Believe it and you will ace THE AUDITION.