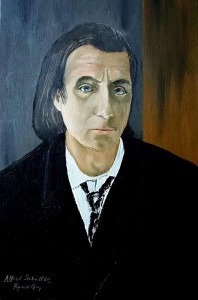

Alfred Schnittke

During the 1970’s, the perceived elitism and dissonant sounds of atonal academic modernism were gradually giving way to artistic expressions that favored a synthesis of familiar styles. By reintroducing traditional elements of musical styles—openly influenced by popular music and world music traditions—composers sought to close the gap between themselves and the listening public, and hoped to restore music to its former position as the language of emotions. Throughout his career, Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) uncompromisingly combined multiple styles and techniques of music with the intense emotional depth of his life experiences. Although born in the Volga-German Republic of the Soviet Union, Schnittke received his earliest musical training in Vienna, while his father served there as a translator. The family moved to Moscow in 1958, and after graduating from the Moscow Conservatory, he immediately banged heads with Soviet doctrine. Resilient in the face of government pressure, Schnittke somehow managed to sustain a career by scoring state-sponsored films, and teaching part-time at the Moscow Conservatory. And in the process, he developed a distinctive “polystylistic” sound of his own.

“My musical development took a course similar to that of some friends and colleagues,” he writes, “across piano concerto romanticism, neoclassical academicism, and attempts at eclectic synthesis, and I also took cognizance of the unavoidable proofs of masculinity in serial self-denial. Having arrived at the final station, I decided to get off the already overcrowded train and proceed on foot.” Merging elements of serialism, pastiche, Romanticism, church music, popular and ethnic music with scraps of historical materials, Schnittke creates startling sound vistas. As the composer puts it, “I set down a beautiful chord on paper—and suddenly it rusts.” In essence, the historical musical landmarks of the past are under immediate pressure from the present. Recalling his days in Vienna, Schnittke is particularly fond of metamorphosing sound bites ranging from Haydn to Schubert, and mingling them with rich veins of aggressive dissonances. These stylistic modulations are never arbitrary or random, but describe a progression from chaotic polystylism to heartfelt spirituality.

Alfred Schnittke: Moz-Art a la Haydn

Schnittke’s extraordinary ability to fragment and reassemble diverse components in new and unexpected ways is amply demonstrated in his 1977 Moz-Art à la Haydn, scored for two violin soloists and small ensemble. The historical building blocks, among others, come from an unfinished humorous pantomime Mozart wrote in 1783, of which only the first violin part and some sketches have survived. Also fleetingly mentioned are Mozart’s Symphony No. 40, and Haydn’s Farewell Symphony. The work opens with the performers—seated in total darkness—improvising around the Mozart pantomime material. Once the lights come on, a diminished chord prepares for the introduction of the neoclassical material. Musicologist David Fanning had suggested “Schnittke treats Mozart with the detached bemusement of a visitor from outer space confronting an artifact from a dead civilization.” Recognizable forms and colors are turned into kaleidoscopic hallucinations, forcing the listener to mentally fit all the pieces back together again. At the end of the piece—just as in Hadyn’s Farewell Symphony—each player leaves the stage one by one, with only the conductor staying behind to beat time. Historical classifications have become meaningless, and in live performances, the parody works on both a visual and aural level. Here as elsewhere, Schnittke traverses the musical spectrum—in the words of the New York Times—with “extraordinary virtuosity, wit and flair.”