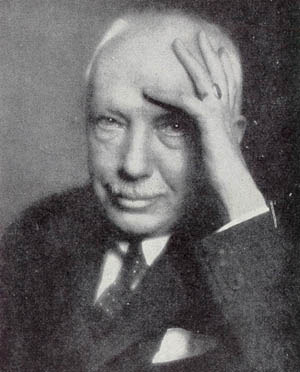

Richard Strauss

Credit: alexanderstreet.typepad.com

The work, initially titled “Held und Welt” (Hero and World) began to take shape in April 1897. Surprisingly, these early drafts labeled “longing for peace after the struggle with the world, refuge in solitude: the Idyll,” emerged while he was working on Don Quixote. In fact, Strauss always considered Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben companion works, and even suggested that they should be performed together. Strauss never fancied himself a mythical hero, but used the vocabulary of heroism to explore the struggles within him. Ein Heldenleben is not merely a musical portrait of an artist’s personality, ideas, domestic life, and career, but rather an allegorical work, “reflecting Strauss’s preoccupation with the Nietzschean ideology of an individual’s right to self-determination in the face of a hostile world.” When Strauss was brusquely asked to explain the militaristic and grandiose surface of the work, he disarmingly replied, “Beethoven’s Eroica is so little beloved by our conductors that I decided to write my own heroic piece in the same key as compensation.” In truth, the work grew from far more personal impulses, including the profundity of domestic love and his relationship with his wife Pauline. For all its philosophical ambitions and militaristic rhetoric, Ein Heldenleben is inundated with multiple layers of irony and parody that marks the end of Strauss’s 19th-century tone poems. Above all, however, it reflects a composer at the height of his creative powers.

The work is divided into six continuous sections that follow the general contours of sonata form, and Strauss willingly clarified his programmatic intentions for each part.

1) “The Hero” A noble, confident and widely spaced melody in unison of strings and horns initially presents a rather one-dimensional portrayal. However, almost immediately an intensely complex character emerges. Dense counterpoint, ingenious development of themes and motifs, powerful rhythmic momentum and a highly original orchestration describes the alert, aspiring, determined yet whimsical eccentricity of Strauss’s Hero. The music forcefully builds towards a might cadence, but is interrupted by

2) “The Hero’s Adversaries” Despite his enormous professional successes, Strauss felt great bitterness towards his critics. In this section of Ein Heldenleben, Strauss takes savage revenge on his detractors. Rasping staccato figures supported by chatty woodwind figuration portray his critics as “petty, spiteful, and insignificant philistines.” At the same time, openly spaced intervals in the tubas disclose their pompous and pedantic qualities. Strauss does his utmost best to musically ignore his nagging adversaries, until a fanfare-like figure demands his full attention.

3) “The Hero’s Companion” This compelling portrait of his wife Pauline de Ahna, is musically encoded in a long cadenza for the concertmaster. Strauss offers a realistic yet tender musical representation of his beloved, a woman he was married to for more than half a century. “Every minute is different from what she was a minute before,” Strauss once confided in a friend. And the solo-violin part exquisitely mimics this assortment of moods, ranging from “hypocritically languishing, merry, frivolous, sentimental, high-spirited, sharp, playful, amiable, angry, and nagging.” Finally, the music passionately swells into a “love scene” disclosing the depths of his feelings and the profound satisfaction he received from domestic life.

4) “The Hero’s Deeds of War” The disturbing cries of the critics are heard in the distance again, and the reluctant Hero answers the call to arms. Snare drums and trumpets initiate cacophonous battle music that develops motifs and themes from the previous three parts. Urged by his companion, the hero contrapuntally opposes the thematic antagonists, who eventually collapse under the sheer weight of the Hero’s motives. When he triumphantly rides across the battlefield, the hymn of victory, rather tellingly, is the heroic theme from Don Juan. Norman del Mar writes, “In his exultance the Hero presents to the whole world excerpts from his mightiest conceptions.”

5) “The Hero’s Works of Peace” Victorious in battle, the Hero returns to his creative work and composes his musical resume. In a dreamy episode, Strauss presents the most dizzying recollection of themes from previous tone poems, opera and lieder primarily concerned with love themes related to the Hero’s partner. Using roughly thirty quotations, Strauss forges a binding connection between creative productivity and domestic harmony, yet the critics return once more.

6) “The Hero’s Flight from the World and the Fulfillment of his Life” The Hero’s final retirement is once more disrupted by a brief surge of battle music. However, the detractors are simply ignored, and the hero indifferently walks away. As such, the ending of Ein Heldenleben remains ambivalent, with Strauss suggesting that the solutions to the cosmic mysteries of life are “found at home, in his work, and with his beloved companion at his side.”

Richard Strauss: Ein Heldenleben , Op. 40