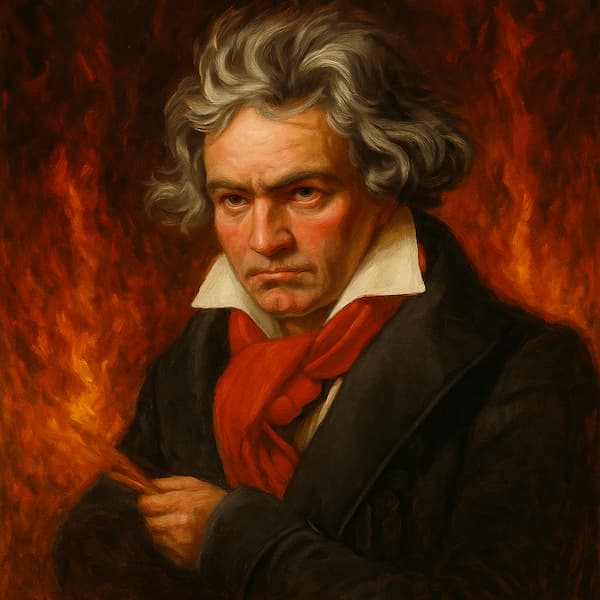

Credit: Wikipedia

An Alpine Symphony, Op. 64, TrV 233

The beauty of this is that instead of being faced with an insurmountable Kilimanjaro of music, you’re left with something a bit more manageable, perhaps a not-so-daunting Snowdon. Of course, it’s unlikely that Strauss had north Wales in mind when composing this piece, but as soon as music has a story connected to it, all you do is follow the musical journey, sometimes literally; after all, this is describing a mountain trip. Which mountain he’s depicting we can’t be sure exactly, but it doesn’t really matter; the flavour of the Alps comes across very clearly.

The piece opens with a B-flat minor chord that gradually unfolds across the whole string section, every player holding a different note of the scale, meaning that eventually there’s a dense, shimmering texture against which the trombones and tuba begin what turns into the sunrise, a glorious B-flat major outburst.

Our travellers set off at a brisk pace, and we hear a robust theme in E-flat major, one that will come back again and again throughout the course of the piece. We come across a party of hunters – but only in the distance. Strauss calls for an offstage group of brass players to give the illusion of another group of people somewhere else in the mountains.

After this energetic opening, the pace slows gradually as we enter the wood, leading to a stroll by the brook. Never content with staying somewhere for long, Strauss picks up the pace, leading us to discover a waterfall, represented by cascading strings and woodwinds, where we glimpse an Erscheinung (water nymph) through the glittering spray of water.

Drying off our clothes, we take a stroll through an Alpine meadow, with flowers (wind, harp and pizzicato strings) dotting the landscape, leading to the pasture – one of my favourite moments. Here, Strauss goes all out on orchestration, representing cows, sheep, birds, yodelling, and anything else you’d care to think about whilst walking through an Alpine pasture, in addition to cowbells. Real cowbells. What’s so clever about this section is that it would be so easy for things like the cowbells and birdsong to be gimmicky, but Strauss weaves them into the rest of the orchestra to create an expansive, almost cinematic, musical texture.

All the while, we’re hearing snatches of themes and motifs previously stated, which tie the piece together and make sure we don’t lose our way up the mountain paths. Incidentally, that’s pretty much the name of the following section, as the travellers wind their way confusingly upwards to arrive at a glacier. Here, Strauss uses dense counterpoint (instruments imitating each other at short distances, often overlapping) to represent the confusion and mounting tension.

Following some dramatically dangerous moments of mountainous ascent, we reach the peak of the mountain, a moment of calm, just before the triumphant music we heard at the beginning of the piece (the sunrise) makes a reappearance. After this winds down, the sun gradually gets obscured and we hear the first drops of rain of what will turn into one of the most supercharged musical storms of all time. Strauss employs full orchestral forces here, in addition to a wind machine, and an organ (for that added extra bit of terror). As the travellers run back down the mountain, we hear little bits of the themes we heard before in short snatches (not fully of course, as we’re running for our lives at this point, and have more important things to worry about), until the storm finally subsides. The sun sets slowly, and the opening B-flat minor haze descends to bring the journey to a close…

With 22 sections of music, the hour or so it takes to perform this piece flies by, as every section has such a distinct character, always moving the drama of the story forward. Although it’s not performed that often because of the 100-ish musicians it requires, seeing this piece performed live is quite an experience, and I’d recommend it: all the thrills of a mountain holiday, no walking boots necessary.