All work !

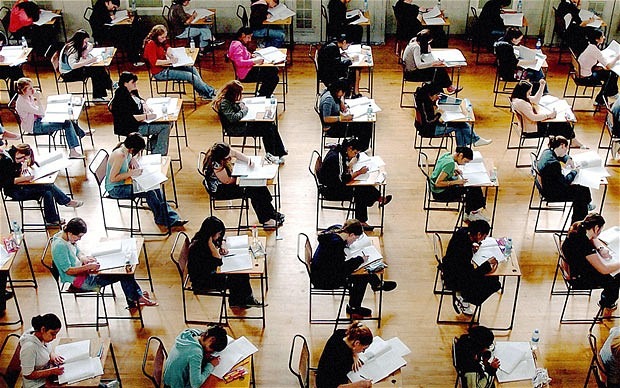

The degree at Cambridge, known as the ‘Tripos’, is structured in such a way so that you begin with set papers that give you a grounding in the general aspects of the course. After this, the choices broaden in later years to allow increasing specialisation as the Tripos continues (much like many other Cambridge undergrad degrees). Your final exams are the only ones that count towards your degree – the first two years are designed to help you prepare for your finals, and thus count for nothing. This end-weighted design of the course can be fairly stressful, but by the time you’ve reached your final year, you’re so used to the exams that it’s not that big a difference knowing they count for everything. Well, that’s the theory…

And play.

You then have the option to continue keyboard studies further in year two with the advanced keyboard skills paper, which begins to mirror the job of a repetiteur. You start to learn more advanced score reading techniques, in addition to transposing whole songs at sight. But this is just an option – the only compulsory papers in second year are analysis and a portfolio of tonal compositions. Whereas there were no options in first year, you begin to gain flexibility in what you study, and you can cover a wide range of bases! For example, in second year I chose a paper on 14th and 15th notational practices, did a dissertation on Daphnis and Chloe, and took an exam on ‘popular music and society’.

Cambridge University

So, ‘Enough of the dry stuff!’ I hear you cry. ‘What about performance?’ You can do an optional recital in third year, which is as equally weighted as the other written papers. But, it’s only optional. A lot of people are astounded at this. How can you spend three years studying music and get away without performing a single note?!

The answer to that is fairly simple, in that the course at Cambridge is (as you’d perhaps expect) a highly academic one. Musicology is a different discipline to performance, with the former deserving no less attention than the latter. It’s possible to inform your performance with skills acquired from studying analysis and music history, in the same way that knowledge of live performance gives life to otherwise abstract theoretical ideas – it’s a pretty symbiotic thing. So, there you have it. Maybe it’s not such a daft idea to tap dance about the Taj Mahal after all. Now, where did I put my dancing shoes…