Hans Werner Henze: Das Floß der Medusa

French artist Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) created his larger-than-life-size painting Le Radeau de la Méduse (The Raft of the Medusa) in 1818 and 1819 to commemorate the wreck of the French naval frigate Méduse. It ran aground off the coast of today’s Mauritania on 2 July 1816. A raft was constructed and set off on 5 July 1816 with 146 people. By the time it was found and rescued 2 weeks later, only 15 people were still alive.

Géricault: The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819 (Paris: Louvre)

The wreck was an international scandal, and the French captain came in for blame for his incompetence. Géricault was fascinated by the accident and prepared himself for his painting by interviewing 2 of the survivors and making sketches. In order to get the skin tones of the dead and dying correct, he visited hospitals and morgues.

The final painting was enormous: 491 by 716 cm (16 ft 1 in by 23 ft 6 in). It was exhibited in the Salon of 1819 and was Géricault’s outstated launch to his career. It garnered both praise and condemnation but brought Géricault to the world’s eyes. It is considered an important early work in the development of the French Romantic movement in painting.

The Medusa was on a political mission to Senegal, where the newly appointed French governor of Senegal was going to accept the return of the country to France from Britain. The Medusa passed the other three ships it was in convoy with and then drifted 160 miles off course to run aground on a sandbank. Efforts to get the ship off were unavailing, and the 400 passengers took to the 6 ships boats. The boats only had space for 250 people. 146 people took to the raft, which promptly partially submerged under the weight. The raft was supposed to be towed by the 6 boats but was let loose after a few miles when it proved to be too much of a liability, dragging the boats back out to sea. When the ship was rescued by the brig Argus, part of the original convoy, only 15 people were still alive, the rest having been ‘killed or thrown overboard by their comrades, died of starvation, or had thrown themselves into the sea in despair’. The entire affair was a tremendous scandal for the newly restored French monarchy; the captain had been a political appointment rather than a merit appointment.

The design of the painting is a pyramid. The pyramid starts on the bottom left with a horizontal group of dead and dying figures. At the point of this pyramid stands two crew members who desperately wave clothes to attract the attention of the ship barely visible on the skyline.

Géricault: The Raft of the Medusa, 1818–1819, detail (Paris: Louvre)

The viewer’s eye starts in the middle and then explores the edges of the raft. The Argus rescue ship is barely visible on the skyline, and it’s only later that the threatening wave at the left top is seen. The painting is dark and sombre and uses a brown palette that, for Géricault, represents tragedy and pain. The only bright light is at the horizon, whence comes the rescue ship.

Géricault’s preparation for the painting extended to more than interviewing two of the survivors, the surgeon Henri Savigny and the geographer Alexandre Corréard, who wrote a book about the disaster (it was suppressed by the censors but published abroad and smuggled back to France). He also constructed a scale model of the raft, including the gaps between the boards. He went to the seaside to look at the sea and sky, even crossing the English Channel to study the elements.

He captured the first view from the raft of the Argus. Despite the optimism and energy in the picture, it was replaced by despair when the Argus passed them by, not seeing them. Two hours later, however, the Argus returned and rescued the remaining 15.

The raft, as depicted by Géricault, includes more corpses than were there at the time of rescue. He also added the stormy scene as the rescue was accomplished on a sunny morning and a calm sea.

In 1965, Northwest German Broadcasting (NWDR) approached Ernst Schnabel and asked him to write ‘a serious oratorio’ with Hans Werner Henze. Schnabel thought of using the survivor’s book and Henze agreed. Both saw in it the potential for an allegory about hierarchies and their propensities for injustice and repression. A political allegory, which both deemed timely, so The Raft of the Medusa was born in the 20th century.

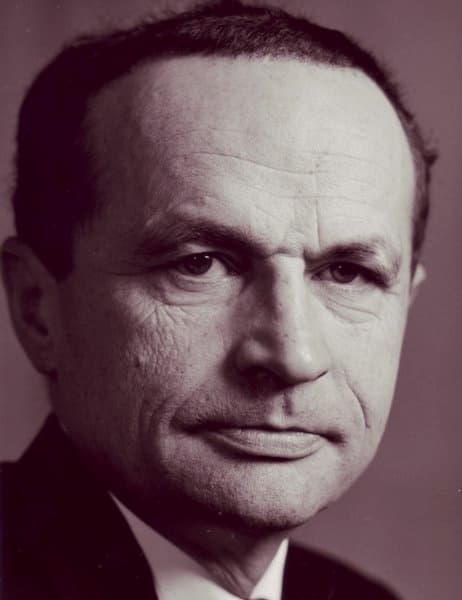

Ernst Schnabel

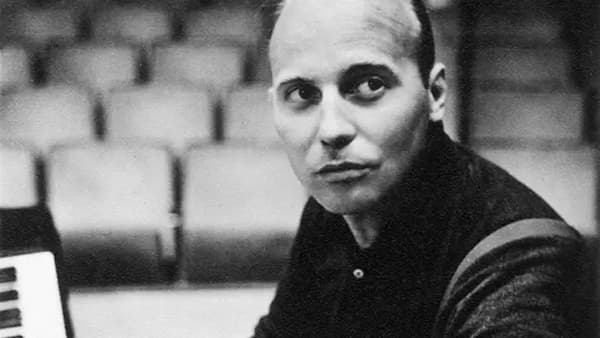

Hans Werner Henze

Henze’s ‘Oratorium volgare e militare’, as he originally subtitled it, was written between 1967 and 1968. Using a Baroque musical form suited Henze as he saw ‘classical ideals of beauty’ in the old forms. Schnabel drew in many references besides the original Savigny and Corréard diary. The dead are evoked from lines from Dante’s La Divinia Commedia, a motto from French philosopher Blaise Pascal’s Pensées is used. Schnabel also adds additional figures to the rafter who were present but invisible: Death (a soprano) and Charon (a speaker), the ferryman of Hades. The only other solo voice is Jean-Charles (baritone), the African sailor who is waving the red handkerchief in the painting.

In the Ballad of Betrays, Jean-Charles tells of seeing the ‘executioner’ in the boat ahead rise and cut the tow rope with an axe (01:10). The chorus immediately comments. This permits everyone to comment, ‘Now there is mercy only for the gentry, the pursers, the cooks, lieutenants, clerks, and the provost’. Death sings at the end.

Hans Werner Henze: Das Floß der Medusa – Part I: Ballade vom Verrat: Wir schauten auf (Dietrich Henschel, Jean-Charles; Sarah Wegener, La Mort; Vienna Boys Choir; Arnold Schoenberg Choir; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Cornelius Meister, cond.)

At the end of the opera, Jean-Charles dies, waving his red flag. He asks death for comforting words: do ships sink there? No, they fly. Do stones fall? No, they rise. Does time count there? No. The work ends with Charon telling of their rescue, concluding with ‘those who did survive, having learned a lesson from reality, returned to the world again, eager to overthrow it’.

Hans Werner Henze: Das Floß der Medusa – Part II: Finale: Schau auf! (Sarah Wegener, La Mort; Dietrich Henschel, Jean-Charles; Sven-Eric Bechtolf, Charon; Arnold Schoenberg Choir; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Cornelius Meister, cond.)

Over the course of the opera, the choir, one by one, moves from one side of the stage to the other – an effective visualisation of Schnabel’s text.

Henze’s political stance brought problems to the premiere. To be held on December 9, 1968, the premiere was disrupted. The work was dedicated to the recently assassinated Ernesto Che Guevara (died October 1968). Students clashed on the night of the performance, some seeking the work to be presented and others seeking to prevent it. Portraits of Che Guevara were hung in the hall and were just as quickly torn down, and it was one red banner hung from the conductor’s podium that caused the choir (RIAS Chorus from the American Sector of divided Berlin) and the Northwest German Broadcasting (NWDR) Symphony Orchestra to say they would not perform under a red flag. Henze refused to remove the red podium banner. In the end, Henze was unable to conduct, the audience stood around and argued and fought until the police were called. Those arrested, including the librettist, Ernst Schnabel, were roughed up as they were taken out. The premiere was cancelled, and Henze had to leave through a back door. The performance, which was supposed to be a live broadcast, was replaced with a recording of the dress rehearsal. The red rag in the hands of Jean-Charles was only a small part of the political effect of the oratorio.

Che Guevara poster

The work finally received its premiere on 29 January 1971 in a concert performance and was staged in Nürnberg on 15 April 1972. Henze revised the work in 1990, and it has been performed many times since then, including a performance in 2006 by the Berlin Philharmonic led by Sir Simon Rattle.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter