Inspiration Behind Robert Saxton’s The Resurrection of the Soldiers

For England, WWI was a devastation—it’s agreed that the country lost its best and brightest, and life after the war has never regained the power and glory the country held.

English painter Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) studied in London at the Slade School of Art and quickly developed his own style, focusing on works with multiple figures. He was born in the village of Cookham and used the village as the focus for many of his paintings. An early series depicted Biblical scenes as set in modern-day Cookham, such as this of a woman hanging out her laundry – or is it Veronica and Christ?

Spencer: St Veronica Unmasking Christ, 1937 (Stanley Spencer Gallery)

Or The Resurrection, as set in Cookham’s churchyard.

Spencer: The Resurrection, Cookham, 1924–1927 (Tate Britain)

In 1915, Spencer started his war service as an orderly at Beaufort War Hospital in Bristol. He was then sent to Macedonia to serve with an ambulance unit before requesting transfer to an infantry unit. He was active for two and a half years on the front line in Macedonia. Recurrent bouts of malaria invalided him home, where he continued painting.

In 1919, Spencer was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee for a painting for their Hall of Remembrance. The Hall was never built, and the art works destined for it went into the national collections. Spencer’s painting, Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing-Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916, reflected his wartime experience and is in the Imperial War Museum.

Starting in 1920, Spencer worked a number of painting series, including works for the private oratory of the Slesser family. Those works inspired Louis and Mary Behrend to commission Spencer for a group of paintings as a memorial to Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham, Mary Behrend’s brother, who had died in Macedonia of an illness during the war. The commission came in 1923; he started work in 1927 after the chapel building was complete and finished in 1932.

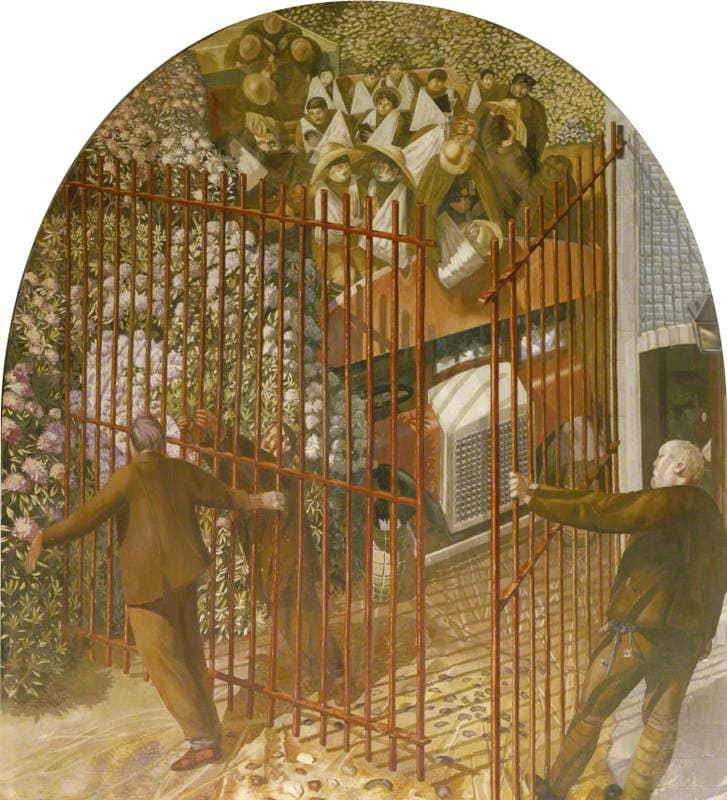

The seventeen paintings are chronicles of Spencer’s everyday experiences in the war, from the arrival of the wounded,

Spencer: Convoy Arriving with the Wounded, 1927–1932 (National Trust, Sandham Memorial Chapel)

the day’s laundry,

Spencer: Sorting the Laundry, 1927–1932 (National Trust, Sandham Memorial Chapel)

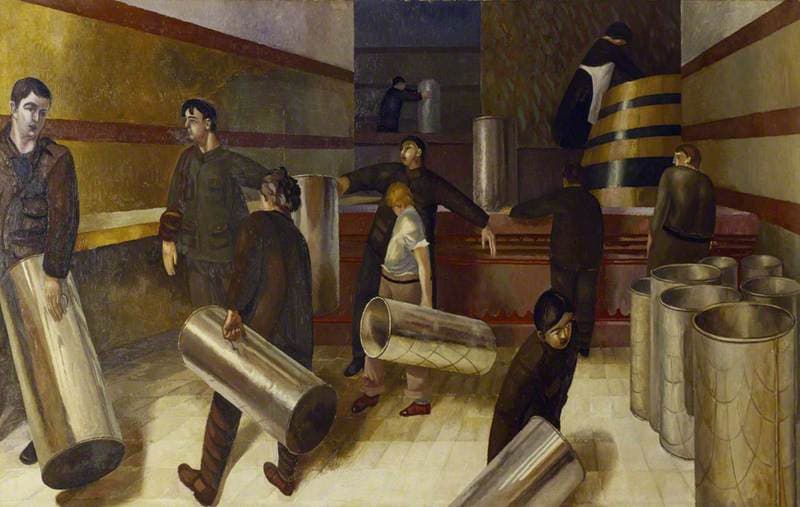

filling tea urns,

Spencer: Filling Tea Urns, 1927–1932 (National Trust, Sandham Memorial Chapel)

and making the beds.

Spencer: Bedmaking, 1927–1932 (National Trust, Sandham Memorial Chapel)

Other images are set on the wards or involve soldierly duties: reveille, kit inspection and map-reading exercises.

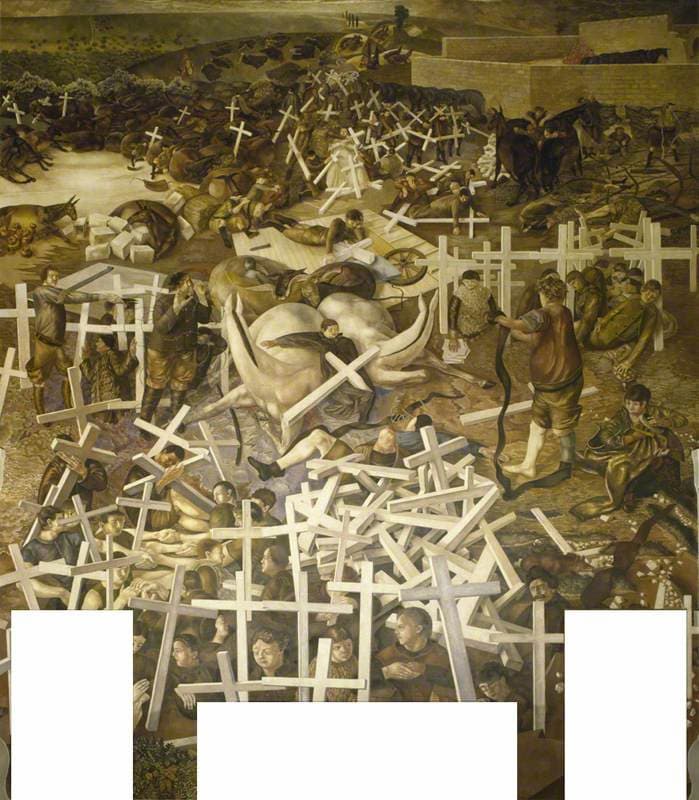

The major work, however, is on the back wall of the chapel and is Spencer’s vision of what could happen after the war. The Resurrection of the Soldiers, much like his earlier Resurrection, Cookham, shows the graves opening and soldiers resuming their duties, such as rolling their puttees or cutting barbed wire. The prominent grave crosses are picked up by the soldiers and delivered to Jesus, who stands at the centre in a white gown. The death that so many soldiers suffered is denied in this image – they return to their duties and get on with their lives.

Spencer: The Resurrection of the Soldiers, 1927–1932 (National Trust, Sandham Memorial Chapel)

This image inspired the English composer Robert Saxton to write his own Resurrection of the Soldiers. Commissioned by conductor George Vass, who has been Artistic Director of the Presteigne Festival since 1992, the work was given its premiere at the 2016 Presteigne Festival.

The work for string orchestra starts with the rising of the dead. The soldiers’ new life is presented in a fugue – which is an interesting choice, as fugues are utterly static. Inherent in a fugue is the lack of a chordal progression (such as I to V), which is what makes more active forms, such as sonata form, work. Once the fugue reaches its climax, it’s followed by a slow movement with another rising melodic line.

Robert Saxton: The Resurrection of the Soldiers (English Symphony Orchestra; Kenneth Woods, cond.)

All of this represents the elements in the painting: resurrection, rebirth, resuming life as it was, and, ultimately, hope for a better tomorrow.

Spencer’s paintings recall us to the reality of the day-to-day life of the soldier, which alternates, as one writer put it, hours of boredom and moments of terror. Spencer chose to omit the things that weren’t important to the infantrymen, such as the officers, and a certain dark-haired individual seemed to be everywhere – himself, of course.

Spencer: Self-portrait, 1923 (Stanley Spencer Gallery)

Although he served as a medic on two fronts, Spencer doesn’t show the bloody side of war. A planned painting on surgery was discarded as being, in Spencer’s words, ‘too traumatic’. In the images, his soldiers are not shown shattered but whole, although bandaged and with crutches as needed.

WWI was not, as hoped, ‘the war to end all wars’, but rather the beginning of what seems to be an unending series of wars in the 20th and 21st centuries. Spencer gives us cause to remember the human, rather than the mechanized, side of the war and its consequences.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter