Mexican composer Carlos Sanchez-Guttierrez (b. 1964), who now teaches at the Eastman School of Music, created his work …Ex Machina in 2008 as a work for marimba, piano, and symphony orchestra. He was inspired by different artworks, mostly by the kinetic sculptures of Arthur Ganson (b. 1955).

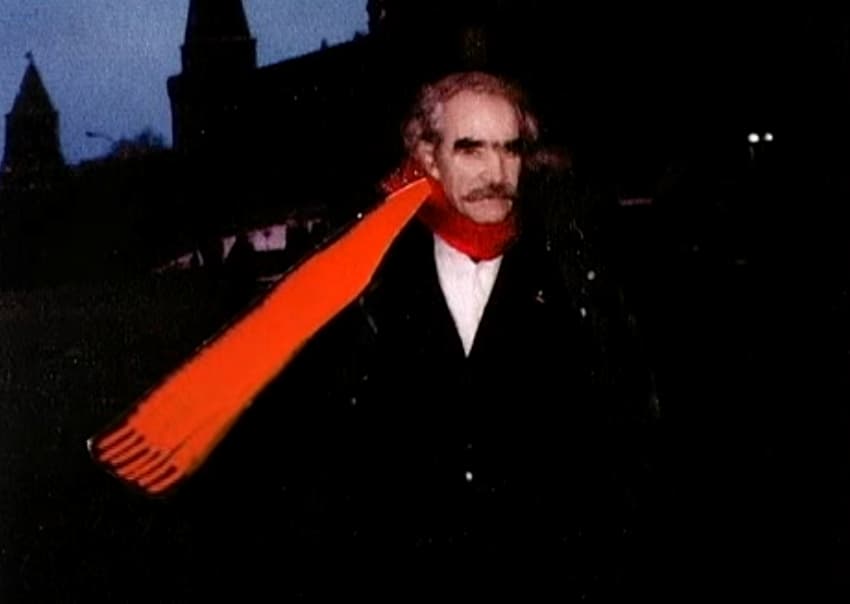

Carlos Sanchez-Guttierrez

Sanchez-Guttierrez sees his composition as a kind of ‘eight-movement circus’ that brings together a number of artworks that are both precisely engineered yet are created with ‘a high degree of precariousness’. They work as you watch them but seem to be barely able to stick together. Their actions are determined and yet wobbly.

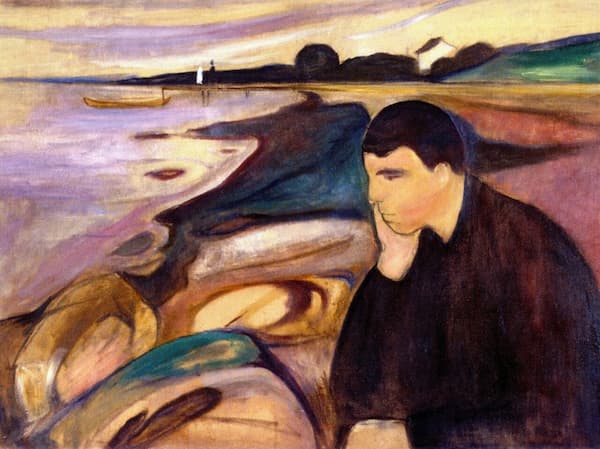

Sanchez-Guttierrez first looked at works by the Dadaist artist Jean Tinguely (1925–1991). This Swiss artist was known for his kinetic machines ((known officially as Métamatics), many of which were intended to self-destruct but might ultimately fail in that goal.

The composer looked at other works, some of which were inspired by Tinguely’s. He starts with Arthur Ganson’s machine in homage to the Swiss kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely in Tinguely in Moscow (In the Wind). The fan blows, and Tinguely’s scarf moves, but the mechanism is more complex than just a fan….

The music for the sculpture brings in more than just the action of the fan – the whole atmosphere of the picture, taken seemingly at night outside some of Moscow’s distinctive buildings around Red Square, comes out.

Tinguely in Moscow

Tinguely in Moscow – Arthur Ganson

In 1989, Australian roboticist Rodney Brooks (b. 1954) created his 6-legged robot Ghenghis at MIT where he was a faculty member. This robot was able to walk, climb over obstacles, and was part of the inventor’s contribution to the discussion of how to make robots intelligent. His robot represented ‘Intelligence without representation’, where it could move around, based not on a pre-determined path, but in reaction to input from the legs’ sensors. There’s no central controller that each leg reports to, so the legs must coordinate their efforts through programming. Genghis now is in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. In his music, Sanchez-Gutierrez starts with Ghenghis’ awakening and follows him through very uncertain terrain.

Rodney Brooks: Gheghis

Rodney Brook’s Genghis Robot First Steps

Arthur Ganson’s Machine with Chinese Fan is a machine designed to open a fan. Although the video shows the fan only opening, the full action of the machine is to both open and close the fan. The artist writes about the sculpture: ‘Intentionally neither animal nor plant, how does it feel to open out to the world? How does it feel to close to the world?’

Sanchez-Gutierrez’s music doesn’t end with the opening of the fan but also includes a long pause so we can appreciate it.

Machine with Chinese Fan – Arthur Ganson

Mexican artist Iván Puig (b. 1977) creates ‘mandalas for the modern life’ out of the objects that surround us. The composer compares his work with drawn mandalas: ‘Mandalas are drawings of concentric figures and repeated patterns around a center, which have served to focus and calm the mind in many cultures’. In this case, for his installation piece mandala I, created in 2006, he uses Don Julio tequila bottles with varying amounts of water in them that each play a different pitch. The hard striker that circles around makes a sharp sound and the light on the end of the striker creates a ‘perpetual counterpoint of light, sound, and movement’.

Sanchez-Gutierrez’ music seems like the quiet backdrop to the clank of the bottles.

Puig: mandala I, 2006 (from the artist’s website)

mandala I

Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez: … Ex Machina (version for piano, marimba and chamber orchestra) – IV. Mandala Tequila (Cristina Valdes, piano; Makoto Nakura, marimba; Eastman BroadBand Ensemble; Juan Trigos, cond.)

In his Machine with Wishbone, Arthur Ganson makes a wishbone walk. For Ganson, the machine and the wishbone are in a symbiotic relationship, each unable to operate without the other. Ganson makes the analogy that ‘we drag our pasts with us and move according to unseen force’ and ‘interface with the world through our mental and technological creations’. The music seems to summon up images of the wishbone’s dragging steps, pushed by the machine yet taking its own path.

Machine with Wishbone – Arthur Ganson

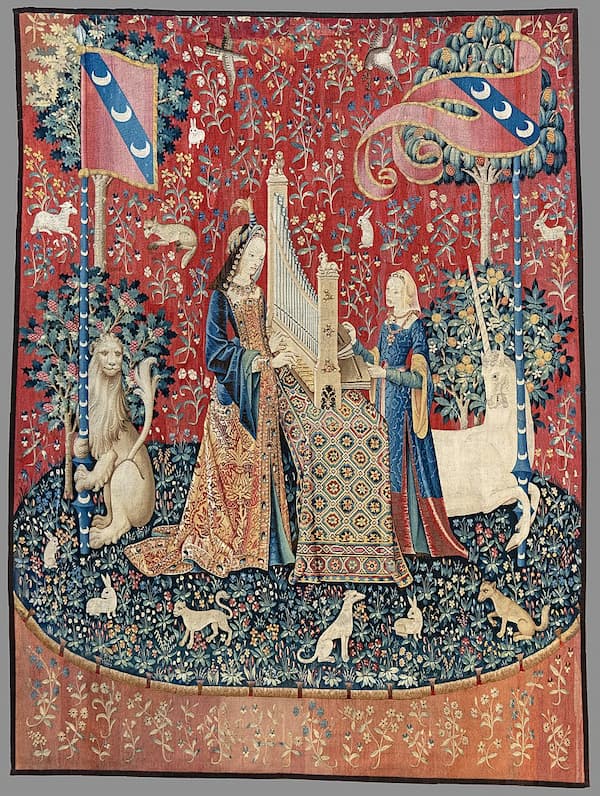

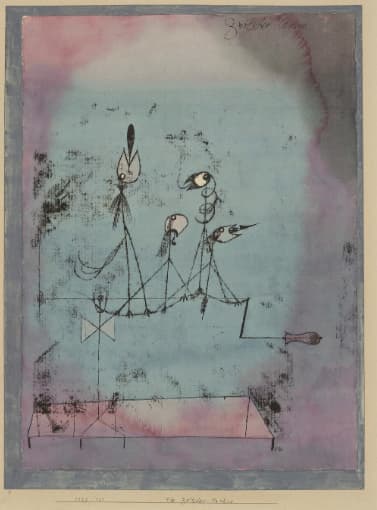

Although Paul Klee’s Twittering Machine from 1922 is a drawing and not a kinetic sculpture, the drawing itself shows machine design: the four birds, three of which are tethered, sit on a curved pole connected to a handle; below them lies a pit. New members who join this choir are in danger of falling into a terrible trap. The image is described as a ‘violent marriage of nature and industry’ designed to ‘mechanize the songs of birds’.

We can only imagine what kinds of sounds the birds might make as they move up and down on the crank. Sanchez-Guitierrez brings the sound of the marimba to the fore at the beginning before the whole mechanism comes to an abrupt halt. It tries to start again and again before the marimba twitters itself into silence. The composer sees the work as dramatic, coming from the systematic but imperfect behaviour of the machine.

Paul Klee: Twittering Machine (Die Zwitscher-Maschine), 1922

(New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Carlos Sanchez-Gutierrez: … Ex Machina (version for piano, marimba and chamber orchestra) – VI. Twittering Machine (Cristina Valdes, piano; Makoto Nakura, marimba; Eastman BroadBand Ensemble; Juan Trigos, cond.)

Greek artist Elias Pierrakos, as part of his degree work in the Animation Program at the University of West Attica in Greece, imagined that in an exhibition of Paul Klee’s art, the lights go out, and Klee’s twitterers come to life. One bird revolves around the crank, and with each revolution, the other birds produce notes. A melody seems to emerge as the crank moves faster and faster until it all stops.

The Twittering Machine

Arthur Ganson makes yet another improbable walker out of an artichoke bracht.

Artichoke (photo by Jamain)

Ganson said that he tried, unsuccessfully, to cook an artichoke in a microwave oven. One result was a single petal that looked like a bi-pedal walker. He says, ‘it moves carefully and with determination’.

The music also has that same care – whatever may be happening in the machine below, the petal walks on. Sanchez-Guitierrez describes Ganson’s machines as ‘simple and profound, quiet and eloquent, high-tech and low-tech, finite and eternal’.

Machine with Artichoke Petal #1 – Arthur Ganson

The work closes with the largest of the kinetic sculptures: Peter Fischli (b. 1952) and David Weiss; (1946–2012) 1987 sculpture The Way Things Go. Rockets, fire, water, gravity, levers, flaming comets, balance, and imbalance are all part of the work. The work has been described as ‘post apocalyptic’ as the chain of objects sets up strings of actions where things fly, crash, burn, or explode. The two video excerpts below are from a 30-minute film of the structure in motion, self-destructing as it unravels. The artists used common household items: tea kettles, pots, many old tires, wooden ramps, and tracks, balls, and balloons to create a sculpture 100 feet long. In his music, Sanchez-Gutierrez echoes some of the visuals: sharp actions and long waits for reactions.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss, The Way Things Go, 1987, Excerpt

The Way Things Go

Ganson says about his sculptures: The edge between crystal clarity and complete ambiguity is a catalytic space for the mind to dream. These machines are meaningless apart from that which the observer brings to them. In this way, every piece is unique, and all interpretations are true. For Sanchez-Guitierrez, these artists can be placed together because even with works of seriousness, they ‘have the secret of lightness’.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter