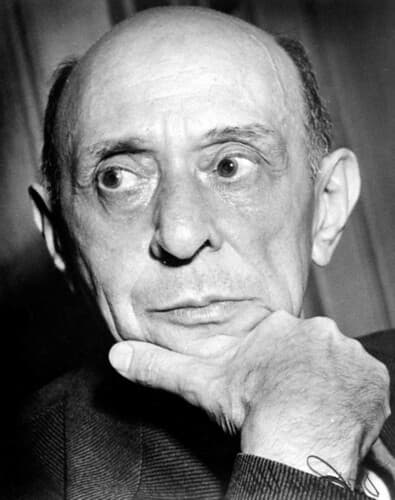

Gustav Mahler

In November 1901, Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) first met Alma Schindler, Vienna’s most eligible Bachelorette. Stepdaughter of the painter Carl Moll, Alma took painting lessons from Gustav Klimt and composition lessons from Josef Labor and Alexander Zemlinsky, with whom she also had a passionate affair. In fact, during their first meeting at a private dinner party, Gustav and Alma engaged in a heated argument over the merits of Zemlinsky’s fairly-tale opera Es war einmal (Once upon a time), which Gustav was conducting at that time.

Unable to settle their differences, they did agree to meet at the Hofoper (Imperial Opera) the following day. A whirlwind courtship soon ensued, and Gustav proposed marriage on 21 December 1901. The couple was formally married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902, with Alma already carrying their first child, Maria Anna. A second daughter, Anna Justine, was born on 15 June 1904. Despite serious reservations from family and friends, who on one side questioned the considerable age gap — she was nearly twenty years his junior — and on the other, criticized the “flirtatious and unreliable nature” of the bride, the couple enjoyed a brief period of extreme happiness. Concurrently, Mahler’s professional career as a conductor had gradually blossomed. Having assumed the directorship of the Imperial Opera in Vienna in 1898 — undoubtedly the world’s most prestigious musical post — Mahler’s productions elicited high praise from audiences and critics alike. His association with the supreme stage and costume designer Alfred Roller spawned more than 20 celebrated productions, and his administrative involvement restored financial stability to the organization. Although his Viennese tenure — which would last until November1907 — was a period of repeated battles with performers, administrators and a hostile press, it nevertheless represented one of the most satisfying decades in his professional life. In addition, his own compositions received more frequent performances, and while his symphonies only gradually gained public acceptance, his songs were comparatively well liked. Given his personal happiness and professional success, how are we to explain the meaning of his Sixth Symphony, one of the most disturbing, menacing and unrelenting compositions to emerge from Mahler’s imagination?

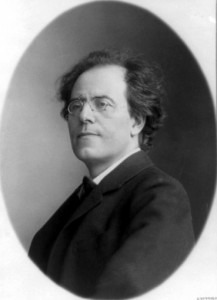

Alma Mahler

London Symphony Orchestra

Valery Gergiev

Mahler began work on his Sixth in the summer of 1903. Taking his holiday in the tiny village of Maiernigg on the Wörthersee — located in the Austrian province of Carinthia — he quickly drafted two movements and eventually completed the work in 1904. Supremely confident in his craft, Mahler hoped that this new symphony would further convert audiences to his music. In the event, however, it was flatly rejected, and the Viennese critic Heinrich Reinhardt quipped “Brass, lots of brass, incredibly much brass! Even more brass, nothing but brass!” Clearly, the public rejection of this work was not simply a matter of orchestration, but emerged from the tragic and bitter pessimism contained in the music. This pessimism was clearly not a reflection of his personal life, but an expression of the enormous political and cultural changes that flooded Europe in the first decade of the 20th Century. As the dismantling of political, social and artistic structures inexorably accelerated towards the catastrophes of two World Wars, Mahler’s music “expressed the intuitive forebodings of an artist listening to the distant rumbles of the future and, as such, formulated the apprehensions of the suppressed and inarticulate.” Albert Camus poignantly stated, “when I describe what the catastrophe of modern man looks like, music comes into my mind — music of Gustav Mahler.” And it is the juxtaposition of Mahler’s prophetic visions of death and destruction with his idyllic personal love for family and nature that gives rise to an outpouring of emotions in a symphony tightly constrained by classical formal procedures and thematic unification. This uneasy duality emerges with brutal energy and conviction in the opening movement, as it juxtaposes a menacing march-like first theme with a broad and tender theme supposedly representing Alma. When the celeste and strings sound a transfigured chord sequence with cowbells ringing in the distance, we have reached, according to Mahler the “most remote loneliness.” Given the earnestness with which Mahler went to task on his Sixth Symphony, it is somewhat surprising that he could not decide on the order of the middle movements. The autograph and first printing placed the “Scherzo” before the “Andante,” whereas Mahler’s own public performances and the second published edition reverses that order. Mahler apparently changed his mind once more, yet the debate as to the correct order of movements still rages. The concluding “Allegro” provide us with a terrifying glimpse of the future. Up to this point, the music had been sharply defined. Now, however, it descends into a nebulous chaos as strings recite aimless musical fragments that brutally collide with the major-minor motive sounded in the trumpets and trombones. Slowly growing in intensity and incessantly driving towards an overwhelming climax, the music is cut short by the brutality of the infamous hammer blow of fate that Mahler wanted to sound like the “stroke of an axe.” Fearing that he would tempt Fate, Mahler removed the third, and final hammer blow. From there, fragments of eerie funeral tunes are sounded in the low brass over extended drum rolls that plunge the movement into utter darkness, all ending in the deepest despair and gloom. Mahler had created “an essential heritage for the future,” but he could not foresee that fate would deal him a triple blow barely a year of the symphony’s first performance. First, his oldest daughter would succumb to diphtheria, he would lose his job at the Imperial Opera in Vienna, and doctors would diagnose him with a severe heart condition.