Maurice Ravel

Claude Debussy

Danses sacrée et profane

Maurice Ravel

Introduction et Allegro

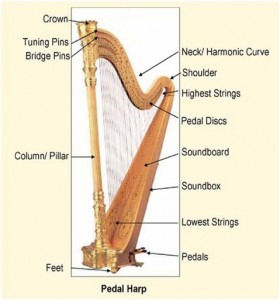

The main difference between the two harps was that the chromatic harp (made by Pleyel) had one string for each chromatic note – much like a piano – whereas the Érard model only had seven strings per octave, and used seven pedals to chromatically change the length of each note of the scale. So, for example, all the C’s on the harp would either be flat, sharp, or natural – you couldn’t play a C-natural against a C-sharp at the same time.

To put salt in the wound, it turned out that Debussy’s piece was entirely playable on Érard’s harp. Not only that, but Ravel’s was absolutely impossible to execute on Pleyel’s. Oops. Not hard to see why the pedal harp won out, and is the harp we see in common usage today.

Claude Debussy

The incredible thing here, along with many other parts of the piece, is that it almost feels like an entire orchestra is playing, rather than just seven people. It’s Ravel’s fantastic instrumental writing that gives it this feel.

Rather than the accompaniment having boring long notes, Ravel makes use of the string instruments’ abilities to cross strings (moving the bow rapidly over each of the four strings) to bring a real vitality to the accompaniment, meaning the music always has life.

Pedal Harp

The following slow section brings back the opening themes, and after this the music grows more and more agitated, with all the themes heard so far interacting in close proximity with each other. The music builds and builds to breaking point, and culminates with a fortissimo diminished chord, with the harp swooping up and down with the use of its glissando.

We then come to the harp cadenza, where Ravel really shows us what he can do with Pleyel’s opponent. It’s undoubtedly the most intimate moment of the whole piece, and at just under 2 minutes of the piece’s 10-minute duration, makes up a significant portion of the music.

Chromatic Harp

Ravel saves a brand new texture for the end of the piece – solo harp with entirely pizzicato accompaniment. Almost sounding like clockwork, the music ticks along, then grows in intensity to a triumphant G-flat major climax.

No-one really seems to have written anything for this combination of instruments since. It’s almost as though this ensemble only exists for this showpiece – as a symbol of the competition between the main two harp manufacturers of the day. However, it’s also a beautiful piece – a hidden masterpiece of twentieth century instrumental chamber writing. Nothing’s been sacrificed in order to show the superiority of the pedal harp over its chromatic cousin. You never feel as though Ravel is going out of his way to show us what the instrument can do; it just does it, and it works.