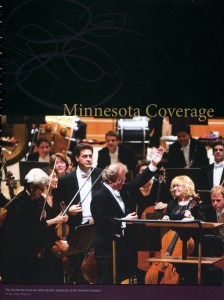

Orchestra on tour

Once again I was the baby of the section and had to prove myself. Jamieson wrote nothing but the bowings in the parts. He must’ve performed the entire symphonic repertoire hundreds of times hence no fingerings. I on the other hand, was learning music new to me every week. When I gingerly approached the subject of putting in a few fingerings in the otherwise unmarred part—after living with the greens, blues, and reds of Shirley’s parts in Indianapolis— Jamieson said it’d be ok if I made a few pencil markings as long as it was tiny, lightly done and under the staff.

Robert Jamieson

To Jamieson’s credit, he encouraged me to perform concertos with the orchestra, a privilege not extended to the associate player very often. He was a wonderful supportive stand partner and never hesitated to advise me.

When he retired, Anthony Ross became principal cello of the Minnesota Orchestra. By this time I was a veteran too. Tony, a wonderful cellist, is very tall, athletic and burly, who towers over me. He also is an “in your face” kind of person who occasionally has to restrain himself from sassy outbursts. We were a great pair who complemented each other. His playing is robust, assertive and vigorous; mine is nimble, artful and polished. Often during performances we would amuse each other with virtuosic fingerings always trying to outdo each other. Our smiles and obvious rapport made our audiences wonder if we were married. (Actually Tony’s wife Beth sits on the second stand and is also a fine cellist.) If need be, I would try to mollify him with our ongoing humorous interchanges if he was annoyed at a conductor or colleague.

Tony needed a lot of room. He would come out onto the stage before a performance and kick chairs out of the way. I would just wait to fit my petite self in once he had the room he needed. Our stand too of course had to be higher to accommodate him. But these issues were minor. The mutual respect between us resulted in frequent consultations about the bowings and best fingerings or phrasing. We would often practice together just the two of us to make certain that we were precisely in tune—our intonation flawless and interpretation unified.

Anthony Ross

On tour to Japan several years ago we all had piano-stool-like chairs, which adjusted in height. Somehow the back of Tony’s formal tailcoat got caught in the mechanism and when we stood for our bow up came the chair with him. I fumbled to disentangle him. Our Japanese conductor was more familiar with these chairs. He leapt off the podium to release Tony who whispered, “ That’s the last time I let you touch my tail.”

Tony and I both performed as soloist many works of the standard literature. His interpretations of the Elgar and Lalo concertos and Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade are standouts. He was equally supportive when I performed Korngold Cello Concerto, Shostakovich, Haydn and Max Bruch’s Kol Nidre.

Sometimes stand partners do not get along, then performing and compromising can be difficult. I feel very fortunate that we not only were compatible personalities but also that we made great music together.

I loved reading this, Janet. Not a concert goes by, when I’m in attendance, that I don’t miss you sitting beside Tony – such a loss for our wonderful orchestra. Keep writing, my multi-talented friend!

Here, Here Nancy!!! 🙂