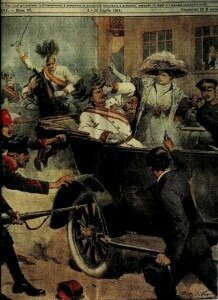

2013 saw the celebrations of Verdi’s and Wagner’s bicentennials, the centennial of Benjamin Britten’s birth and of Stravinsky’s ‘Rite of Spring’. 2014 marks a more somber centennial — of the outbreak of the Great War following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the presumptive heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo. This event became one of the catalysts of the Great War, as nation after nation would slide towards the inevitable. The recently published book, ‘The Sleepwalkers’, by the British historian Christopher Clark is one of the best detailed accounts of the events leading to war. The Great War would unleash such terror — endless carnage in the trenches, gas attacks, shellshock — and would result in the lost generation of those fighting these battles. Having grown up on the French/German border, I remember visiting the haunting battlefields of Verdun, with the endless rows of crosses, the ossuary filled to the brim under the main memorial, and the earth so saturated with metal, that fifty years later, still nothing would grow — trees and bushes distorted, unable to reach their full heights.

2013 saw the celebrations of Verdi’s and Wagner’s bicentennials, the centennial of Benjamin Britten’s birth and of Stravinsky’s ‘Rite of Spring’. 2014 marks a more somber centennial — of the outbreak of the Great War following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the presumptive heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo. This event became one of the catalysts of the Great War, as nation after nation would slide towards the inevitable. The recently published book, ‘The Sleepwalkers’, by the British historian Christopher Clark is one of the best detailed accounts of the events leading to war. The Great War would unleash such terror — endless carnage in the trenches, gas attacks, shellshock — and would result in the lost generation of those fighting these battles. Having grown up on the French/German border, I remember visiting the haunting battlefields of Verdun, with the endless rows of crosses, the ossuary filled to the brim under the main memorial, and the earth so saturated with metal, that fifty years later, still nothing would grow — trees and bushes distorted, unable to reach their full heights.

As part of the centennial commemoration, many concerts in Europe and the United States, billed as ‘peace’ concerts, are planned — one of the most significant will be the concert by the Vienna Philharmonic in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, on June 28, 2014 playing the music of Alban Berg, a soldier in the Austrian army and Maurice Ravel, an ambulance driver for France who served near Verdun. Many writers, painters and musicians fought as patriots on opposite sides, and many of their formerly ‘international’ artists’ associations dissolved, such as the German Expressionist group ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ in Munich, which had included the Russians Wassily Kandinsky and Alexej von Jawlensky and the Germans Gabriele Műnter, Franz Marc and August Macke. Kandinsky and Jawlensky were then considered enemy aliens and were expelled from Germany.

With the fall of empires, a changed Europe would present a very different world to musicians, painters and writers. Its impact in France will be illustrated in this article (Part I of two). As mentioned above, many artists considered it their patriotic duty to fight for their respective motherlands. Lucien Durosoir, violinist and French composer, expressed this sentiment in many letters to his mother, while confronted daily with death on the front, but seeing this sacrifice essential to save his country and its children. His path crossed that of Maurice Maréchal, one of the best-known cellists of the first part of the 20th century, as well as the composer André Caplet, a friend and orchestrator of Claude Debussy’s compositions. Rumors of their extraordinary talents reached the French Commanding General Charles Mangin, a music lover, who considered these artists ‘national treasures’ of such importance that he took them under his protection and kept them away from the front, out of harm’s way. Lucien Durosoir remarked later that the violin had saved his life.

The Belgian violinist and composer, Eugène Ysaÿe, at 56 years of age, had decided to remain at his villa near Oostende (his three sons were already in uniform), but after Belgium mobilized its troops and with the advance of the German army, he decided to leave his villa and join the army — leaving the following note at the door: “This establishment belongs to an artist who lived and worked in the cult of Bach, Beethoven and Wagner”. He gave many violin recitals for the soldiers, reminding them that although faced by death, classical music transcends the horrors of war and through its beauty, hopefully would facilitate supreme universal reconciliation, and would help avoid war in the future.

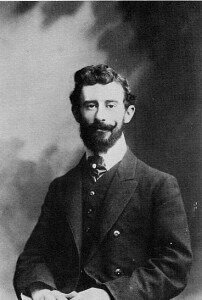

Maurice Ravel

Ravel’s six movements are:

- Prélude — to the memory of Lieutenant Jacques Charlot (who had transcribed Ravel’s piece Ma Mère l’Oye for solo piano).

- Fugue — to the memory of Jean Cruppi.

- Forlane — to the memory of Lieutenant Gabriel Deluc (a Basque painter from Saint Jean-de-Luz).

- Rigaudon — to the memory of Pierre and Pascal Gaudin (brothers, killed by the same shell).

- Menuet — to the memory of Jean Dreyfus (at whose home Ravel recuperated after demobilization).

- Toccata — to the memory of Captain Joseph de Marliave.

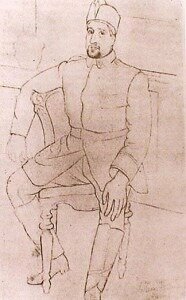

Picasso drawing of Apollinaire

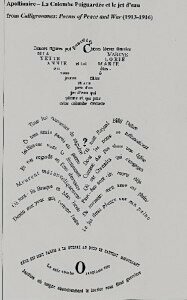

Apollinaire – La Colombe Poignardée et Le Jet d’Eau

In next month’s issue, Part II will address the implications of the Great War on the German and Austrian writers, painters and musicians.