The recent exhibition of ‘Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes’ at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. and several of the recent Interlude articles on the same subject raised interesting and important questions about the connection and inter-relationship between the arts in the beginning of the 20th century. How did Russia’s painters, composers and dancers contribute to one of the most exciting periods in the arts in Europe, influencing music and all of the arts well into our times? How did these extraordinary talents of the Russian dancers, composers and artists develop in Russia? For an answer, we have to turn to the Russia of the 18th and 19th centuries.

The recent exhibition of ‘Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes’ at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. and several of the recent Interlude articles on the same subject raised interesting and important questions about the connection and inter-relationship between the arts in the beginning of the 20th century. How did Russia’s painters, composers and dancers contribute to one of the most exciting periods in the arts in Europe, influencing music and all of the arts well into our times? How did these extraordinary talents of the Russian dancers, composers and artists develop in Russia? For an answer, we have to turn to the Russia of the 18th and 19th centuries.

From the 18th century onward, European artists, architects, composers, painters and dancers had already been part of the Russian court and aristocratic society, particularly after Peter the Great had founded St. Petersburg — his ‘Window to the West’ — in 1703. We also have to remember that from this time on, Russia was part of Europe, for 200 years until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Italian architects, such as Tressini and Rastrelli, the German architects Georg Velten and Andreas Schlueter, and Jean-Baptiste Alexandre LeBlond from France were working in St. Petersburg with Danish and Dutch engineers, supplanted by Russian architects only during the reign of Empress Anna Ivanovna in the latter part of the 18th century. In fact, not only architecture, but all of the arts, literature, music, theater and ballet were, and remain to this day, inextricably linked to St. Petersburg — the true cultural heart of Russia.

And before the younger capital

And before the younger capital

Ancient Moscow has paled

Like a purple-clad widow

Before a new empress

Pushkin

Sleeping Beauty – Pas de six: Adagio

Sleeping Beauty – Act I: Pas d’action: Adagio (Rose Adagio)

Sleeping Beauty – Act III: (b) Adagio

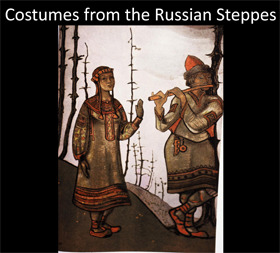

Like architecture and music, Russian ballet was initially modeled on the French and Italian traditions. In the beginning of the 19th century, Russian ballet scenes were typically performed against a backdrop depicting a park. Dancers often wore crinolines and high heels, which did not allow free movement. The performers were serfs — dancers, actors and singers — belonging to wealthy aristocratic families who had their own private theaters. After serfdom was abolished in 1861, many of the most famous artists joined the companies of the Imperial Theatres in Moscow and St. Petersburg — and from then on, Russian ballet started to change. Ivan Valberg, a dancer and ballet master, began the process of synthesizing the Russian performance style with the dramatic pantomime and virtuoso techniques derived from Italian ballet, as well as from the strict forms of the French school, thus shaping a new national Russian school of ballet. The particular interest in folklore and ‘character dance’ would shape Russian choreography and become its distinctive feature. The Khorovod circle dance, with its roots in Russia’s Middle Ages, was performed in Russian villages at the spring equinox, starting at sunrise and finishing at sunset. It provided the inspiration for Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

The French ballet master Charles Louis Didelot (1767-1837) also played an important role in the history of Russian ballet, with his inventive settings in staging, light and scenery. His ballets were based on the one hand, on Russian myths and fairy tales — dance dramas — mixing the tragic and the comic, intertwining pantomime, dialogues and monologues, and on the other, on works of literature, such as Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila, The Overthrow of Chernonov and The Evil Sorcerer.

The French ballet master Charles Louis Didelot (1767-1837) also played an important role in the history of Russian ballet, with his inventive settings in staging, light and scenery. His ballets were based on the one hand, on Russian myths and fairy tales — dance dramas — mixing the tragic and the comic, intertwining pantomime, dialogues and monologues, and on the other, on works of literature, such as Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila, The Overthrow of Chernonov and The Evil Sorcerer.

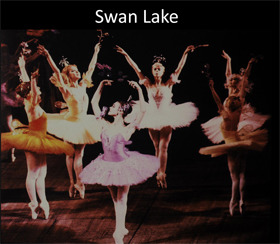

The most significant import for Russia was the Frenchman Marius Petipa (1818 -1910), at first a dancer in St. Petersburg’s Imperial Company (Mariiensky/Kirov Ballet Company), who later became one of Russia’s most famous choreographers. He staged many of the famous ballets (well over 60 in total), such as The Pharaoh’s Daughter (1862), Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, just to name a few — many of which are still amongst the most beloved ballets of all times.

Petipa defined a code of rules for academic ballets; he worked closely with Russian composers, such as Tchaikovsky and Glazunov, symphonizing ballets such as the four adagios of each act of Sleeping Beauty, providing unparalleled examples of poetic expression. His productions were notable for their masterful compositions, their solo parts and pas-de-deux, giving equal importance to male and female dancers. Blending simple and complex movements and inventing new ones, he developed ways to convey moods, character and feelings, gaining in the process a level of craftsmanship that remains to a large extent unsurpassed even to the present for traditional ballets. Rigid patterns of classical dance were enhanced with poetic images and poetic content, always closely tied to the music of the Russian composers. The theatrical backdrops were created by many of the most famous painters of the period, such as Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov, Apollinary Vasnetsov, Nicholas Roerich (set design for Borodin’s Prince Igor) and Alexander Benois.

Petipa defined a code of rules for academic ballets; he worked closely with Russian composers, such as Tchaikovsky and Glazunov, symphonizing ballets such as the four adagios of each act of Sleeping Beauty, providing unparalleled examples of poetic expression. His productions were notable for their masterful compositions, their solo parts and pas-de-deux, giving equal importance to male and female dancers. Blending simple and complex movements and inventing new ones, he developed ways to convey moods, character and feelings, gaining in the process a level of craftsmanship that remains to a large extent unsurpassed even to the present for traditional ballets. Rigid patterns of classical dance were enhanced with poetic images and poetic content, always closely tied to the music of the Russian composers. The theatrical backdrops were created by many of the most famous painters of the period, such as Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov, Apollinary Vasnetsov, Nicholas Roerich (set design for Borodin’s Prince Igor) and Alexander Benois.

Many of these artists were associated with the Arts and Craft movement in Russia, which included the so-called ‘Peredvizhniki’ (Itinerant Painters/Wanderers) — a movement outside the traditional Russian Art Academy. It introduced ideas about a new, real Russian depiction of what real life in Russia was about. Its origins were in the studios of St. Petersburg painters, who moved from painting to creating theatrical decor, laying the foundation for the tradition of Russian theater decor which would reach well into the 20th century.

Many of these artists were associated with the Arts and Craft movement in Russia, which included the so-called ‘Peredvizhniki’ (Itinerant Painters/Wanderers) — a movement outside the traditional Russian Art Academy. It introduced ideas about a new, real Russian depiction of what real life in Russia was about. Its origins were in the studios of St. Petersburg painters, who moved from painting to creating theatrical decor, laying the foundation for the tradition of Russian theater decor which would reach well into the 20th century.

In my October Interlude article, I will continue the investigation of the relationship between the arts in Russia in the 20th century. Only through their arts, in this period of social and political upheaval, could musicians, writers and painters express their personal views, formulating their visions of a new Russian society through their interplay of music, painting and literature.

More Arts

-

Musicians and Artists: Wagner and da Vinci Wagner's massive choral work that echoed through Dresden's Frauenkirche

Musicians and Artists: Wagner and da Vinci Wagner's massive choral work that echoed through Dresden's Frauenkirche -

Musicians and Artists: Byström and Wåhlstrand From vast seascapes to intimate roses

Musicians and Artists: Byström and Wåhlstrand From vast seascapes to intimate roses - Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

Percy Grainger’s Kipling Jungle Book Cycle Transforming Kipling's animal kingdom into music -

Musicians and Artists: Daugherty and Rivera Michael Daugherty transformed Rivera's murals into music with 'Fire and Blood'

Musicians and Artists: Daugherty and Rivera Michael Daugherty transformed Rivera's murals into music with 'Fire and Blood'