Mozart’s relationship to church music has been compared to a child’s attitude towards eating sprouts and spinach. That attitude was clearly conditioned by his troubled interaction with Count Hieronymus von Colloredo, who was appointed Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg in 1771. This dual appointment placed him in charge of the political affairs of the state, and simultaneously recognized him as the spiritual leader of the community. A strict authoritarian, he demanded unconditional obedience from his servants, including Leopold and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who were employed as court musicians. In the spirit of the Enlightenment, Colloredo attempted to banish the influence of secular music genres and dramatic mannerisms—particularly those originating in opera—from church service. Instead he favored music that would humbly serve the demands of the liturgical year.

Mozart’s relationship to church music has been compared to a child’s attitude towards eating sprouts and spinach. That attitude was clearly conditioned by his troubled interaction with Count Hieronymus von Colloredo, who was appointed Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg in 1771. This dual appointment placed him in charge of the political affairs of the state, and simultaneously recognized him as the spiritual leader of the community. A strict authoritarian, he demanded unconditional obedience from his servants, including Leopold and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who were employed as court musicians. In the spirit of the Enlightenment, Colloredo attempted to banish the influence of secular music genres and dramatic mannerisms—particularly those originating in opera—from church service. Instead he favored music that would humbly serve the demands of the liturgical year.

During the initial years of Colloredo’s rule, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart produced a large number of sacred compositions. However, he only partially complied with the musical demands of his boss, eventually leading to a complete breakdown of their relationship. Mozart remained disillusioned for the rest of his life, and in a letter to his father dated in 1783, he sarcastically wrote, “When it gets warmer, please look around in your attic and send us some of your best church music. Everybody knows that the ‘gusto’ is always changing, and that change has unhappily extended even to church music; though that ought not to be—whence it also comes, that real good church music is found—in the attic and worm-eaten.” “Epistle Sonatas,” commonly referred to as Church Sonatas aside, Mozart’s liturgical compositions are spearheaded by the unfinished Requiem. Characteristically, the work is thoroughly steeped in the symphonic-operatic idiom, intermingled with fugues and scored for chorus alternating with soloists, and accompanied by orchestra. Arguably, his most profound effort, however, emerges in a humble sixty-four measure musical miniature.

To prepare for the birth of her sixth child, Constanze Mozart visited a local spa in 1791. Located near Vienna, the small town of Baden had since medieval times provided relaxation and cures for Austria’s ruling families. Her husband, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart meanwhile, remained in Vienna to continue his work on the Magic Flute. For the Christian feast of “Corpus Christi”—celebrated on Thursday after Trinity Sunday—Wolfgang, however, managed to join his wife in Baden. Once there, his personal friend and local church musician Anton Stoll commissioned a setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum corpus (Hail, true body). Mindful of the limited musical forces and abilities at this disposal, Mozart composed a remarkably short and simple setting for mixed choir, string ensemble and organ continuo.

In his setting, Mozart made sure that the words of the Latin text—a poetic meditation on the suffering of Jesus—could be clearly understood. As such, Mozart favored a homophonic texture, in which all voices of the choir articulate the words at the same time. Furthermore, besides providing a brief introduction, transition and ending, the orchestra merely doubles the voices of the choir throughout. Despite its apparent simplicity and brevity—the entire composition only lasts for forty-six measures—Mozart’s melodic and harmonic ingenuity and genius are instantly obvious. Alternating between spacious opening intervals and dense chromatic endings for individual phrases, which are infused by skillful modulations and changes of tempo that musically illustrate the meaning of the text, Mozart managed to compose one of his most moving and intimate compositions. Seemingly searching for a new simplicity of style, the work provides an almost otherworldly sense of peace and tranquility.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Ave verum corpus, K.618 (Hail, true body)

More Inspiration

- Italian Opera in the United States

Lorenzo da Ponte: L’Ape Musicale (The Musical Bee) Meet America's first Italian opera champion! -

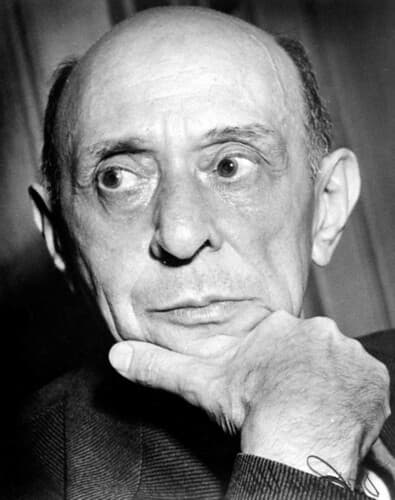

Ode to Napoleon: Byron and Schoenberg How Schoenberg transformed Byron's poem into a musical commentary

Ode to Napoleon: Byron and Schoenberg How Schoenberg transformed Byron's poem into a musical commentary -

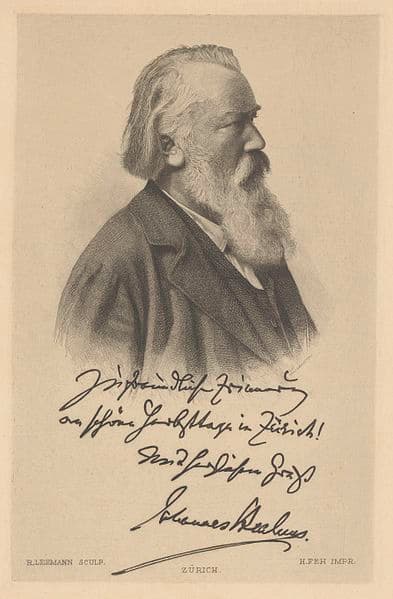

Chamber Music Dedicated to Johannes Brahms Brahms inspired deep devotion from fellow composers, learn more

Chamber Music Dedicated to Johannes Brahms Brahms inspired deep devotion from fellow composers, learn more - Goldfish

“Moving Flowers” Hear how composers captured their graceful movements in sound

Mozart 🙂

I agree entirely with Alicia Baird, but the words of the Latin text are less “a poetic meditation on the suffering of Jesus” than a salute (as the opening word indicates) to His Body, present in the Sacrament of the altar, to be sung on the second feast-day (Holy Thursday being the first) celebrating the institution of that Sacrament; as you say, on the feast of Corpus Christi, known in German as Fronleichnam ‘the Lord’s body’. The principal feast-day of the Blessed Sacrament is Holy Thursday, but instrumental music is strictly forbidden on that day and the two following.