The little girl was seven years old when she awoke and saw a ghost standing beside her. His hair was long and white, and he wore a cassock. He told her that he had been a composer and pianist in life, and that he would return to give her music one day. The little girl remembered the meeting for the rest of her life, but she didn’t know who the man was until she saw a picture of Franz Liszt years later. The little girl was named Rosemary Dickeson Brown; she was a composer; and her story is one of the strangest in music history.

The little girl was seven years old when she awoke and saw a ghost standing beside her. His hair was long and white, and he wore a cassock. He told her that he had been a composer and pianist in life, and that he would return to give her music one day. The little girl remembered the meeting for the rest of her life, but she didn’t know who the man was until she saw a picture of Franz Liszt years later. The little girl was named Rosemary Dickeson Brown; she was a composer; and her story is one of the strangest in music history.

Rosemary Dickeson was born in London in 1916. Her beginnings were ordinary. Her father was an electrician and her mother was a catering manager, and they lived above a dance hall. As a young person, she took intermittent piano lessons. Although sources disagree as to how musically talented she was, nobody claims she was a prodigy or a professional. In 1952, she married a scientist named Charles Brown and had two children with him. Nine years later, dual tragedy struck when both her husband and her mother died.

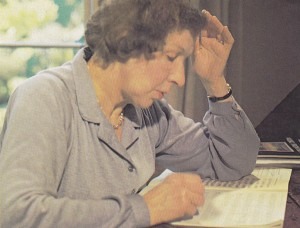

Brown had always been sensitive. (She once said, “I’ve always had the ability, ever since I can remember, to see and hear people who are thought of as dead.”) But the deaths of her mother and husband triggered a new interest in the afterlife, and not long afterward, the man in the cassock reappeared to her. Brown describes the beginning of her work with Liszt in this interview with the BBC:

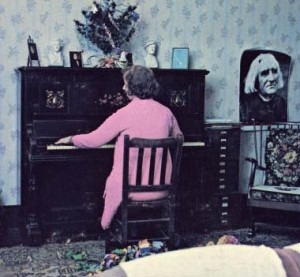

I was actually at home because I’d had an accident at work and broken some ribs, and the hospital had sent me home and said that I must rest, that I musn’t do any heavy housework. And the time was passing very slowly because I couldn’t do very much. And I decided to go to the old piano, which hadn’t been touched for years, and I thought I would sit there and try to remember some little tune which I’d learned as a child. So I sat down and began to try to remember this tune. And then suddenly my hands were controlled by Liszt’s and began to play the most beautiful music, very difficult music.

I was actually at home because I’d had an accident at work and broken some ribs, and the hospital had sent me home and said that I must rest, that I musn’t do any heavy housework. And the time was passing very slowly because I couldn’t do very much. And I decided to go to the old piano, which hadn’t been touched for years, and I thought I would sit there and try to remember some little tune which I’d learned as a child. So I sat down and began to try to remember this tune. And then suddenly my hands were controlled by Liszt’s and began to play the most beautiful music, very difficult music.

Later Liszt also served as a kind of conduit for other composers. Eventually she transcribed pieces “by” Debussy, Rachmaninoff, Schubert, Chopin, Stravinsky, and others. She claimed that each man had a unique style of transmission. Some would press her hands on the keyboard (she appreciated this method; that way, she could actually hear what she was writing), while others preferred to dictate straight to paper. She then had to give pianists the written compositions because she didn’t have the technique to play them herself. In between transmission sessions, the composers interacted with her on a more human level. She claimed that Liszt took an interest in the price of bananas, while Chopin was horrified by television, and Debussy was “a hippie type.”

Fascinated by the work that Brown was producing, Scottish music teacher Mary Firth partnered with Sir George Trevelyan to create a fund so that Brown could quit her day job and devote herself to channeling. Television producers began to take an interest in the quiet widow, who patiently told her story again and again. She composed in front of the cameras for the BBC and even went on Johnny Carson. Eventually she wrote several books about her experiences.

Musicians and psychologists alike were fascinated by Brown’s compositions. (Her fame in the 1960s and 1970s was such that Leonard Bernstein himself visited her!) Some musicians embraced her pieces’ otherworldly origin story. Others were much less impressed. But no one ever came up with a convincing logical explanation for the pieces’ existence. The paranormal visits slowed as Brown’s health declined, and she died in November 2001.

Maybe Rosemary Brown was indeed channeling the spirits of great composers. Maybe she tricked everyone by working with an accomplice, or by seeking advanced musical training in secret. Or maybe her subconscious somehow dictated the works. Regardless, the compositions of Rosemary Brown stand as some of the most unique (and unlikely) ever written.

Chopin – Nocturne As-dur – as dictated to Rosemary Brown June 21st, 1966

If the ‘dead’ can communicate, then there is no reason why they should not communicate music. One of the best contemporary investigators is Professor Gary Schwartz of the University of Arizona. He has mediums in one room and the ‘sitters’ (the person wishing to communicate with the other side) in another room. This eliminates the ‘cold reading’ possibility put forward by Darren Brown and which he demonstrates.