I recently came across an extraordinary image.

I recently came across an extraordinary image.

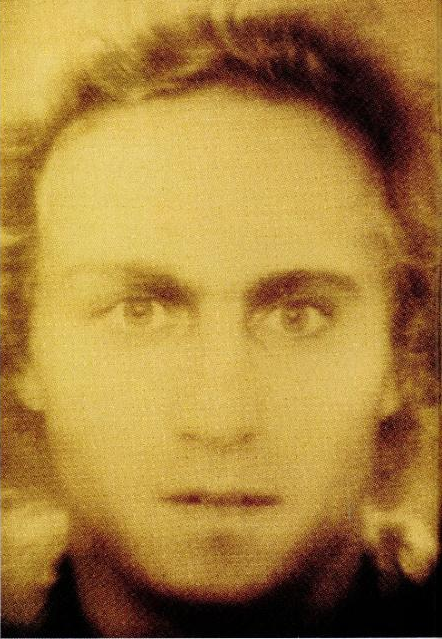

Many police services combine images of a suspect to create a general photo-fit image. But the federal police in Berlin recently combined a number of portraits of a man who died in the late 18th century to create a composite image of his face. Aside from the anachronism of seeing a photograph of a man who has been dead for over 200 years, the photo serves the purpose of bringing him back from the grave – the intensity of his front-on gaze and the detail of his hair and stubble are arresting, and of course so different to the portraits of the time, which were frequently touched up to bolster or alter the reputation of the person in question. Often, their portraits contain references to their occupation or status; a lord would have objects of value surrounding him to demonstrate his wealth, or an artisan the tools of his trade. So to see this man devoid of those trappings, to see him just as a man like any other, is extraordinary considering his status within the canon of Western art.

The man in question is Mozart, the image a ‘real-life’ depiction of his face. The myths around Mozart are plentiful, of course – where did his talent come from? Was he wealthy? Or did he die in poverty? Considering his life story, the photo (which shows him in early middle age) must represent him very near the end of his life – does he seem sickly and pale in the photo, or is that just the greenish tinge? This photograph in an instant cuts through this web of fantasy and conjecture, and forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that Mozart was, despite his achievements, a human like the rest of us.

Composer portraiture is a fascinating subject. Many paintings inform how a composer was perceived at the time; often the mere fact that a portrait exists is telling. One of my favourites, for example, is Haydn, with two portraits of the man telling very different stories. One taken early in his life show the craftsman at work wearing comfortable, but not fine clothing. The second, when he had achieved great fame, show Haydn the public figure, wearing splendid clothes and with paper and ink nowhere to be seen. The transformation in position is evident.

Composer portraiture is a fascinating subject. Many paintings inform how a composer was perceived at the time; often the mere fact that a portrait exists is telling. One of my favourites, for example, is Haydn, with two portraits of the man telling very different stories. One taken early in his life show the craftsman at work wearing comfortable, but not fine clothing. The second, when he had achieved great fame, show Haydn the public figure, wearing splendid clothes and with paper and ink nowhere to be seen. The transformation in position is evident.

So if portraits are informative and enjoyable, what do we make of this photograph? In a broader sense, what is it that we want when we look at a composer? What are we trying to discover? On a simple level there is in our culture a fascination with personality, as evinced by the plethora of interviews with cultural figures that appear every week in newspapers and magazines the world over as well as well-worn but still popular anecdotes. There seems to be a thrill in attempting to permeate the space that exists (most likely self-created) between artist and ‘normal’ human by finding out about the minutiae of their lives – their daily routine, what they have for breakfast and so on. These attempts to get closer are surely indicative of a quest to find out how we ourselves can achieve such status. Perhaps if we change our daily routine, we too will become artists? It’s rarely so simple – though getting up earlier does seem to be a recurring pattern…

Anyhow, this quest is of course doomed to failure. This perhaps explains why what I feel about the Mozart picture, after astonishment and fascination, is disappointment. Portraits of cultural figures present an image to us through the medium of another’s eyes and brushes. The subject itself is at a remove; we can admire from a distance. But a photograph, especially an artless one such as this, places us directly in contact with the subject. Suddenly the mask falls away, and the minutiae dull rather than enliven.

Anyhow, this quest is of course doomed to failure. This perhaps explains why what I feel about the Mozart picture, after astonishment and fascination, is disappointment. Portraits of cultural figures present an image to us through the medium of another’s eyes and brushes. The subject itself is at a remove; we can admire from a distance. But a photograph, especially an artless one such as this, places us directly in contact with the subject. Suddenly the mask falls away, and the minutiae dull rather than enliven.

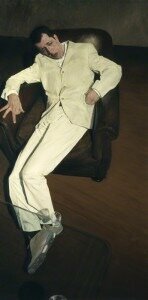

An often-overlooked fact in today’s world of close-up publicity photographs is that artist portraits still exist. One of my favourites is a painting of British composer Thomas Adès in London’s National Portrait Gallery, his anguished faced and languishing body ironically evocative of the torture of the creative artist. The portrait is evocative of the man and his music in a way that no photograph could do, and though the image is somewhat disturbing, I do think I prefer it to the Mozart photo. You should never meet your idols – the richness, allusion and suggestive power of painting creates not just an artificial barrier, but a lens through which we are able to engage with the figure of the artist which, like it or not, is an idea firmly rooted in our 21st century consciousness. Striking as it is, it seems that the Mozart photo undoes the vital distance and commune between artist and audience that is essential to our experience of music today.

An often-overlooked fact in today’s world of close-up publicity photographs is that artist portraits still exist. One of my favourites is a painting of British composer Thomas Adès in London’s National Portrait Gallery, his anguished faced and languishing body ironically evocative of the torture of the creative artist. The portrait is evocative of the man and his music in a way that no photograph could do, and though the image is somewhat disturbing, I do think I prefer it to the Mozart photo. You should never meet your idols – the richness, allusion and suggestive power of painting creates not just an artificial barrier, but a lens through which we are able to engage with the figure of the artist which, like it or not, is an idea firmly rooted in our 21st century consciousness. Striking as it is, it seems that the Mozart photo undoes the vital distance and commune between artist and audience that is essential to our experience of music today.

More Blogs

- Nature versus Love

Béla Bartók’s The Wooden Prince Bartók's brilliant synthesis of influences while remaining uniquely his own -

Why Are We More and More Attracted to Slow Music? Explore how music has evolved from active listening to 'sound decoration'

Why Are We More and More Attracted to Slow Music? Explore how music has evolved from active listening to 'sound decoration' -

Leonard Bernstein’s Children: What Happened to Them? Meet the Bernstein children: Jamie, Alexander, and Nina

Leonard Bernstein’s Children: What Happened to Them? Meet the Bernstein children: Jamie, Alexander, and Nina - John Field

10 Most Beautiful Nocturnes This composer pioneered the dreamy piano style we often associate with Chopin